Homo Sapiens Project

Introduction

Rouzbeh Rashidi has been creating films as part of his Homo Sapiens Project (HSP) since 2000. While this unique approach to filmmaking initially developed unconsciously without a full understanding of the project’s scope, it took him over a decade to truly define and name the Homo Sapiens Project. The prime examples of this philosophy are HSP (200) and HSP (201). HSP (200) was started in 2000 as a work in progress and completed in 2020, with a duration of 490 minutes. Similarly, HSP (201) began in 2002 and finished in 2021, lasting 1150 minutes. These films represent a constant quest for equilibrium and connotation. Each section of the Homo Sapiens Project serves as a form of therapeutic practice, reflecting significant life events, stylistic changes, and thematic shifts in Rashidi’s filmography. They are about peace, a concept rarely existing within Rashidi’s work. The main purpose of the HSP is to explore the medium of filmmaking and cinema itself, while also allowing Rashidi to live and thrive within it.

Rashidi has always felt compelled to create the HSP film series, driven by an unexplainable internal urge. It’s as if he has an idea waiting to be brought to life. As he continues making these films, he realizes they answer questions he didn’t even know were there. Understanding the meaning behind each film can be lengthy, and sometimes, it remains a mystery. Life itself is inexplicably mysterious, and Rashidi believes there is no distinction between filmmaking and living. Therefore, the path of these films takes the shape of an ellipse or a spiral, never a straight line. The straight and linear only exist in geometry, not in the ever-evolving nature of life.

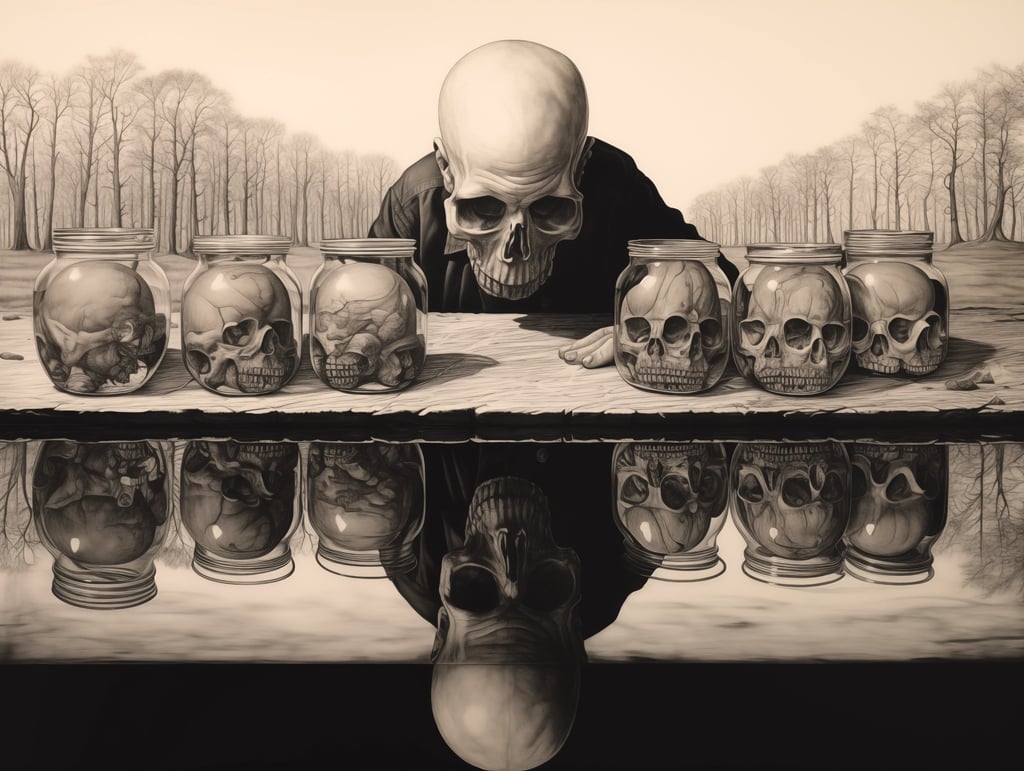

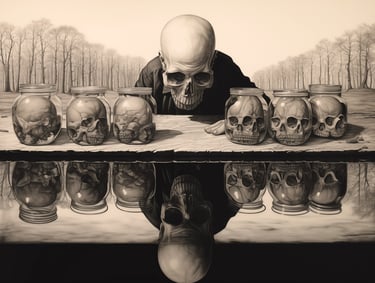

The Homo Sapiens Project, an experimental video series, is the brainchild of Rouzbeh Rashidi. From its humble beginnings as enigmatic film diaries, the series has been evolving over time to refine its craftwork form into feature films. During the Project’s journey, Rashidi has had the opportunity to explore and embrace various experiences while always staying close to the core components of the project — compelling renderings of both people and places imbued with undertones of science fiction, horror, the occult, and associations to post-apocalyptic rituals and dystopian settings. Rashidi has sought out prestigious global contributors, both behind and in front of the camera, to help create and assemble diverse poetics of instalments varying in length and scale.

Authorial Statement

The Homo Sapiens Project (HSP) is the distillation and, in some ways, the culmination of my experimental film practice. I have always been committed to making deeply personal, formally experimental work that collapses the boundaries between alienated subjective perception and the inexhaustible mysteriousness of the moving image. I view cinema (in the broadest sense of the word) as a laboratory and my audio-visual works as experiments in which my own perception and inner life are employed as a ‘reagent’. My work begins with sound and image and works intuitively ‘outwards’ towards ideas. I generally utilise heavily unconventional screenplays or poetic texts, seeing the process of making moving images as exploration rather than illustration. My work is deeply engaged with film history.

HSP is an ongoing series of varied films that provides, first and foremost, a laboratory for experimenting with cinematic forms. Since its inception, HSP has experienced an organic metamorphosis, drastically mutating from cryptic film diaries and oneiric sketches to fully polished feature films. A ‘notebook’ – sometimes an oblique ‘diary’ – HSP radically challenges the traditional mode of filmmaking. It thoroughly explores the potential of filmmaking as an integral and ongoing part of daily life, as enabled by today’s technology. These works are created on low budgets, but they are far from being raw chunks of home movies. Each of them is crafted with great attention to visual qualities and with an idea in mind that, to a greater or lesser degree, makes a foray at the limits of cinematic expression. The films produced range from cryptic, often darkly surreal, film diaries to impressionistic portraits of places and people, from found footage séances to semi-documentary monologues. Formally, they encompass everything from highly composed and distantly framed meditations to frenetically flickering plunges into the textural substance of moving images. They are often suffused with an eerie sense of mystery reminiscent of horror and classic Sci-Fi cinema.

The project HSP will lead to an incomprehensible and unpredictable outcome. Taken as a whole, this will be an opaque and mysterious project: not a life filmed, but filmmaking as parallel to life, and a parallel life a ‘thinking through’ of cinema that will test the limits of the medium to the furthest degree that one artist’s practice can encompass.

Philosophical Statement of the Filmmaker

Homo Sapiens Project: Non‑Teleological Temporality and Cinematic Immanence

Rouzbeh Rashidi's Homo Sapiens Project (HSP) constitutes a sprawling experiment in cinematic form and philosophical inquiry. In lieu of conventional narrative or teleological progression, HSP presents a cinema that interrogates its own ontology – the being and thought of the moving image – through radically non-linear montage, immersive sensory design, and alien perspectives. The project treats film not as a vehicle for storytelling but as a mode of thinking in its own right, probing what images do and are when divorced from human-centred chronologies and meanings. Indeed, as François Laruelle's non-standard philosophy suggests, artistic practices like filmmaking can serve as "methods of thought" that are independent of traditional philosophy. HSP embraces this premise, unfolding as a singular cinematic thought form that engages ontological, phenomenological, and formal concerns at the limits of film. The following analysis reframes HSP through a philosophically attuned lens, eschewing historical narrative in favour of an inquiry into its aesthetic and conceptual structures. Key focal points include the non-teleological temporality of HSP's elliptical montage, the ontology of the image as pure immanence, the decentering of human agency in favour of a "non-human" cinematic consciousness, and the practice of film as an effective mode of knowing. Throughout, an impersonal academic tone is maintained, drawing on a constellation of unconventional philosophers (Coccia, Laruelle, Negarestani, Silverman, Fisher) and experimental cineastes (Deren, Markopoulos, Grandrieux) to illuminate HSP's radical poetic-philosophical project.

Elliptical Montage and Non‑Teleological Time

A defining feature of the Homo Sapiens Project is its abandonment of linear, goal-directed time in favour of non-teleological temporality. The films unfold through elliptical montages – sequences of images and events that often lack overt causal logic or narrative payoff. Instead of driving toward a conclusion or plot resolution, each segment of HSP explores temporal experience as open-ended, circular, or associative in nature. In this respect, HSP aligns with Maya Deren's notion of vertical montage in poetic cinema. Deren famously distinguished between the horizontal development of narrative (where each scene propels the story forward) and the vertical accumulation of emotional or symbolic intensity in experimental film. In Meshes of the Afternoon, for example, Deren constructed a montage "held together by an emotion or a meaning that [the scenes] have in common, rather than by the logical action". Likewise, Rashidi's HSP favours associative rhythms and recursive motifs over linear plot progression. Scenes are linked by echoes of tone, visual rhyme, or affective undercurrent rather than by chronology or character-driven causality. This yields a temporality that is qualitative and intensive – time measured in moods or sensations – rather than quantitative or teleological. The viewer is invited to dwell in the duration of images, experiencing their recurring patterns and subtle variations, without the expectation of narrative closure.

Such an approach produces a cinematic time that is an-archic (without a ruling beginning or end) and often cyclic. Episodes of HSP sometimes loop or return to earlier imagery in a way that resists any final conclusion. One account of the project describes the viewer "stumbling through the dark forests of Rashidi's Twilight Zone that is rife with Sisyphean loops" – an allusion to mythic endless repetition. These "Sisyphean loops" signal that the films do not build toward a teleological resolution but instead continually restart the journey of perception and thought. Instead of a narrative "arrow" of time, HSP offers time as depth, with layers of memory, dreams, and references coexisting in a perpetual present. In some instalments, a single quotidian situation is replayed with variations or interrupted by inexplicable temporal jumps, unsettling our usual sense of past and future. The editing frequently employs elliptical cuts, omitting intermediate actions and allowing temporal gaps. This technique – familiar in avant-garde practice as a way to compress or disjoin time – here becomes a philosophical device: it severs the expectation that each moment must lead to the next, thereby freeing each image to exist for itself. The result is a non-teleological montage in which sequences evolve according to an inner poetic logic rather than any external endpoint or story.

Crucially, the renunciation of teleology in HSP is not merely a stylistic play but carries ontological implications. By suspending the usual cause-and-effect narrative chain, Rashidi's films foreground being over becoming. Each shot or scene is presented as a kind of self-subsistent reality – an occurrence whose significance is immanent, not deferred to some later payoff. This approach aligns with experimental film traditions that treat time as circular or wholly present. We might think of Gregory Markopoulos, who championed "film as the film" beyond storytelling conventions: he realised that the most profound cinematic experiences lay outside the linear narrative, asking, "Who can dare to imagine what a single frame might contain?". Markopoulos's rhetorical question suggests that a single image, in its vertical depth, may carry a world of meaning without requiring narrative sequencing. HSP operates in this spirit. Its elliptical montage opens spaces for contemplation within and between images rather than rushing the viewer along to the next plot point. Scenes often linger beyond the point of narrative necessity, drifting into oneiric or meditative temporality. Moments of apparent stasis or repetition become opportunities for the viewer's mind to roam – to contemplate the image in its immediate affective and visual richness. In HSP's temporal structure, meaning is not a destination but emerges in the act of viewing, in the span of time spent with an image. The absence of teleology thus invites the viewer into a more phenomenological experience of time, echoing Deren's assertion that breaking from linearity encourages us "to contemplate the meaning and what [we're] feeling" in each moment.

The Image as Immanence: Ontology of the Cinematic Frame

With narrative scaffolding stripped away, the image itself in the Homo Sapiens Project assumes an ontological primacy. Rashidi's cinema asks: what is an image in itself when not subordinated to representation or story? HSP posits an ontology of the moving image as pure immanence, meaning that the image exists on its own plane of reality, co-extensive with the world rather than reflecting something transcendent or external. This view resonates with certain philosophical re-conceptions of the image in recent thought. For instance, Kaja Silverman argues that the photographic image is not a mere copy or index of reality but rather "the world's primary way of revealing itself to us". In Silverman's account, an image originates in what is seen (the world's visibility) rather than in the human eye; it is an "ontological extension" of the real, an analogy that shares being with its referent. HSP's handling of imagery exemplifies this principle. The films present their visuals – whether a landscape, a face, or a texture of light – not as pointers to an underlying message or story but as things in themselves, worthy of attention in their own right. A dilapidated room bathed in eerie light, an abstract pattern of grain on celluloid, a human figure in extreme close-up – such images in HSP confront the viewer with their sheer presence, their being-there before any interpretation.

Emanuele Coccia's philosophy of images provides another fruitful lens. Coccia suggests that images play a cosmological role, forming a continuum between living beings and their environment, thereby erasing any strict division between subject and world. According to Coccia, "media in the cosmos… produce a continuum in which the living and their environment become inseparable," and thanks to images, "matter is never inert… and the mind is never purely interiority". Images, in this view, are "true cosmic transformers" that bridge the spirit and matter. HSP's corpus often literalises such ideas. The boundary between the camera and the world, or between the human observer and the environment, dissolves in these films. In HSP, the camera lens becomes almost osmotic: light, atmosphere, and movement flow into the recording medium, yielding images that feel less like representations and more like imprints of reality's own processes. We frequently sense that the film is capturing not a human drama but a material or elemental one – clouds roiling, water shimmering, vegetation encroaching – as if the world is expressing itself through moving images. In one volume, for example, a tranquil park scene is filmed "through the eyes or rather, visual receptors of a mysterious being/entity who may be the incarnation of cinema itself". Although we know Rashidi is behind the camera, the resulting images give the uncanny impression that cinema itself (or the world itself) is looking. The image here is immanent to an alien or non-human viewpoint embedded in reality rather than anchored to a human protagonist. This strategy emphasises that each image carries its own meaning as an emanation of an impersonal visual reality.

In treating images as immanent presences, HSP joins an avant-garde lineage that insists on the autonomy and depth of the cinematic image. Gregory Markopoulos's aforementioned ethos of film as film – and his marvelling at what might be contained in a single frame – finds an echo in Rashidi's frame compositions. The microscopic attention to the grain, colour, and duration of each shot in HSP suggests that, indeed, every frame teems with potential meaning. Markopoulos's films of the 1960s, characterised by "ecstatic 'chords' and clusters made of the shortest visual elements" and an "eerie sense of colour and rhythm", sought to liberate cinema from referential storytelling and let the image speak on its own terms. HSP adopts a similar stance: images do not illustrate a script or serve a narrative telos but instead form a poetic continuum of impressions and energies. The project's use of visual abstraction, superimposition, and lens distortion further reinforces the notion of image-as-immanence. At times, we see figures and landscapes dissolve into grains of light or fields of colour, pushing the image to the threshold of the non-representational. These experiments invite ontological questions: Where does the image end and reality begin? Is the filmic image a window onto reality or a slice of reality itself? HSP seems to answer by collapsing the distinction – the image is a reality, one layer of the world entering into the sensorium of the viewer.

Rouzbeh Rashidi's statements underscore the inexhaustible being of the cinematic image. He speaks of "the inexhaustible mysteriousness of the moving image", implying that no matter how much one analyses or narrativises an image, something remains opaquely itself – an immanent mystery. This mysterious surplus is not a problem to be solved but the very point of HSP's aesthetics. By dwelling on images that resist immediate intelligibility, the films cultivate a sense of immanence: the meaning of an image is not behind or beyond it but within it as a constant potential. We might draw a parallel to Nicole Brenez's description of the work of another experimental auteur, Philippe Grandrieux. Brenez observes that Grandrieux's filmic imagery "works to invest immanence under the species of sensation, of impulse". In other words, his films plunge the viewer into the pure sensation of the image, treating the image as an affective reality rather than a signifier. She further notes that "the propensity of bodies to immanence" appears to be "the raison d’être" of Grandrieux's films, meaning that the films exist to explore how bodily experience (of light, colour, movement) can be conveyed directly, without mediation by narrative or symbolism. HSP operates with a comparable mission. Across its many instalments, it consistently privileges presence over-representation: the grainy flicker of footage, the play of shadows in monochrome, the "beautifully composed images" inhabited by an enigmatic atmosphere – all these are presented as immediate realities to engage with, not code to decipher. In sum, the ontology of the image in HSP is one of radical immanence. The cinematic frame is treated as a living cell of reality, a locus where matter and meaning coincide. The viewer is encouraged to encounter each image on its own terms, to sense in it the same depth and openness one finds when observing the world directly. In this way, HSP elevates the cinematic image from a vehicle of storytelling to an ontological event—a happening of being and perception that unfolds in the here and now of viewing.

Cinema Beyond the Human: Non-Human Perspectives and Thought-Forms

Extending its exploration of immanence, Homo Sapiens Project also challenges the anthropocentric orientation of mainstream cinema. Rather than anchoring the films in a human protagonist's gaze or a director's didactic message, HSP often adopts what can be called a non-human perspective – a mode of cinematic vision and thought that is not centred on individual human subjectivity. In practice, this manifests as eerie, quasi-objective camerawork and narrative absence of any conventional "hero" through whom the audience experiences the story. Instead, the camera itself – or some unnamed presence behind the camera – becomes the protagonist. The series is pervaded by the feeling that an alien consciousness is observing human life and environments, collecting impressions without fully entering into human motives or speech. Indeed, one volume of HSP is explicitly described as "an anthropological study conducted by the very same alien factor whose presence is strongly felt throughout this peculiar anthology". Here, the film itself behaves like an alien researcher: under "disturbingly motionless clouds" in a public park, everyday people (children playing, lovers talking) are filmed with a detached, inscrutable curiosity. The suggestion is that an "alien factor" – invisible yet palpable – is "collecting data for itself or maybe its superiors". Such framing decouples the cinematic viewpoint from any known human identity, positing instead a non-human agency behind the camera eye.

This strategy aligns HSP with certain strains of philosophical thought that speculate about non-human thought or inhuman perspectives. A vision of "inhumanism" in which trustworthy rational agency is "not personal, individual, or necessarily biological". In Rashidi's view, reason can operate as an impersonal force, "a revisionary power" that transcends the human self-portrait and even works through non-human systems. Translating this idea to cinema, HSP tries to decenter the source of cinematic meaning from the human to the inhuman. The films often feel as if they are being thought by the camera or by the environment itself rather than narrated by a human storyteller. For example, in HSP (1), the kitchen interior is filmed so strangely that, as noted earlier, it appears to be seen through the eyes of "a mysterious being… who may be the incarnation of cinema itself". This conjures the impression of cinema as a non-human thought form – as if the medium has its own alien cognition that perceives the world differently than we do. The human characters within the frame, including Rashidi himself in occasional appearances, are rendered as just one part of the image's overall texture, not privileged bearers of meaning. In one sequence, Rashidi's distorted figure walks across a red carpet under a fisheye lens, an image that is presented as a "conclusion" yet resists any personal narrative explanation. The effect is that even when the filmmaker enters their film, they become another object among objects, absorbed into the film's immanent vision rather than serving as its controlling subject.

Through such techniques, HSP cultivates an experience akin to what cultural theorist Mark Fisher terms the eerie – "a failure of absence or a failure of presence" - that unsettles our assumptions about agency. Fisher defines the eerie feeling as occurring "when there is something present where there should be nothing or nothing present where there should be something" and notes that this perspective can "give access to the forces which govern mundane reality" by revealing the strangeness underlying the familiar. In HSP, the eerie arises precisely from the sense of an undefined presence behind the camera (something present that usually isn't) and the notable absence of human-centred narration or explanation (something absent that generally would be there). The viewer becomes conscious of the unknown observer – that "enigmatic presence" which "perseveres in its intents to alienate the viewer from the worldliness of… images". Everyday scenes are made strange; the banal is rendered in "hyper-realistic" detail yet feels unearthly as if filtered through intelligence that is studying it coldly or ritualising it. This estrangement of perspective has the paradoxical effect Fisher describes: it breaks the veneer of familiarity. It lets us see the reality onscreen as if from outside, "as outside of us, as inhumane and somehow alien". In one HSP segment, for instance, long static shots of ordinary spaces (train stations, hotel lobbies) are held so that their normal human occupants almost disappear in the distance; the architecture and ambient noise come forward, evoking what Fisher would call "the eerie underside" of the everyday. We start to sense impersonal structures – of environment, of capital, of technology – ghosting the scene rather than empathising with any individual in it.

The non-human vantage of HSP is further reinforced by formal choices that deny viewers the usual anchors of human-driven cinema. Dialogue is minimal or entirely absent in most instalments; when present, it is often obscured, distorted, or treated as just another sound among the soundscape rather than a carrier of the plot. Faces of actors, including Rashidi, may appear but often without the cinematic cues that invite identification or emotional alignment (we might see a face in an extreme close-up, disembodied, or a figure in a long shot moving anonymously through a landscape). In place of narrative guidance, HSP supplies a rich, often disorienting audio-visual ambience that the viewer must navigate without guidance – much as an alien intelligence might survey human life with fascination but without insider understanding. We could say that HSP practices a kind of phenomenological dehumanisation, not in a moral sense but in a methodological one: it brackets the human as just one element of the lifeworld, not the measure of all things. This brings to mind François Laruelle's project of "non-philosophy," which attempts to think from a radically non-hierarchical perspective he calls the vision-in-One, where no standpoint (not even the human philosopher's) claims sovereign Truth. John Ó Maoilearca (John Mullarkey), interpreting Laruelle, notes that non-philosophy "opens the door for other methods of thought, including filmmaking and other artistic forms as thought". HSP can be seen as an instantiation of this idea: a non-philosophical cinema that generates thought without centring on a human philosopher or protagonist. It is as if the films themselves think that by assembling images and sounds, they pursue lines of inquiry about perception, reality, and memory in an inhuman register. In the process, HSP questions anthropocentric habits of seeing. It asks whether a film can express ideas that no character articulates and reveal truths that no human author dictates by letting the camera be a quasi-autonomous explorer of immanent reality. The answer HSP provides is implicitly affirmative: through its alien gaze and eerie detachment, it discovers a cinematic mode of thought that is parallel to human reflection yet not limited by it. This is cinema as a non-human thought-form – a reflective practice of the moving image itself, on its own plane of material and optical interactions.

Film Practice as Affective Epistemology

If HSP posits cinema as a form of thought beyond the human, what kind of thought is this? The experience of watching the Homo Sapiens Project suggests that it is not a discursive or analytical thought but an affective and sensory one. In other words, HSP approaches film as an affective epistemology: it produces knowledge or insight through the viewer's affective experience – through mood, sensation, and emotional intensity – rather than through exposition or argument. The films do not convey philosophical ideas; they embody them by inducing states of mind and emotion in the audience. This strategy aligns with a broader turn in experimental aesthetics towards understanding art as a way of knowing that is embodied and affect-driven. As such, HSP can be fruitfully read in dialogue with thinkers who have emphasised affect, sensation, and feeling as modes of understanding.

One immediately notable aspect of HSP is how it deliberately disorients the viewer and then uses that disorientation productively. The fragmentation of narrative, the non-human perspective, and the unpredictable editing all serve to destabilise our usual cognitive bearings. Yet this destabilisation is not total: Rashidi often introduces patterns, motifs, or even moments of humour and beauty that re-orient the viewer at a new level. The critic Nikola Gocić, writing on HSP, observes that "Our disorientation – an integral part of the filmmaker's grand design – is alleviated by the playfulness of the moving images". The films intentionally throw the audience "out of our comfort zone" with jarring cuts, uncanny imagery, or opaque sequences but then "comfort us back" with absorbing audio-visual rhythms or moments of meditative calm. In this ebb and flow of confusion and captivation, the viewer undergoes a kind of sensory training. HSP's cinematic world often has the logic of a dream: discontinuous but held together by an atmospheric and emotional coherence. The viewer learns to feel their way through the film, trusting the affective cues (sound textures, colour tones, repetitions) as guides to meaning when rational plot cues are absent. In a sense, the meaning of HSP crystallises in these affective responses: the slow dread of a long take, the sudden jolt of a cut to an unexpected scene, and the sublime calm of a static landscape after a period of chaos. Such feelings are the content; they prompt the audience to reflect on states of being – e.g. what does it mean to experience boredom, anxiety, eeriness, or wonder in a pure form, outside of a narrative cause?

We can relate this to the idea that film can think by embodying thoughts as sensations. Maya Deren hinted at this when she suggested that poetic (vertical) cinema "encourages the viewer to contemplate… what they're feeling" rather than following what is happening. In HSP, contemplation emerges from the viewer's affective immersion. For example, a sequence may envelop us in droning ambient sound and dim visuals for several minutes, inducing a trance-like state. This trance is not mere ambiguity; it is pregnant with insight. It might evoke, for instance, the feeling of being lost in time or the awareness of one's own act of seeing. At times, HSP explicitly plays with trance and dream states, echoing the legacy of trance-film in the avant-garde (as in the works of Deren or Anger). The goal, however, is not to mystify but to use altered affective states to probe reality from another angle. A viewer entranced by the film's slow, rhythmic oscillations may find their mind drifting to new associations, perhaps realising connections between disparate images or sensing a hidden order in what first seemed chaotic.

The interplay of affect and understanding in HSP finds theoretical support in certain strands of contemporary thought. For instance, Mark Fisher's analysis of the eerie (discussed above) implies an epistemic function for effect: the eerie feeling alerts us to gaps in our knowledge (a presence unaccounted for, an absence unexplained). It thereby directs us to deeper forces at work. In HSP, scenes of uncanny calm – such as an empty hallway with faint echoes or a field where an unseen figure might lurk – create a sense of expectation and uncertainty that prompts the viewer to question what is really occurring beneath the surface of the image. Fisher observed that by dwelling in such affective uncertainty, "we break through the veneer of familiarity" and perceive structures (social, material, temporal) that typically remain hidden. Similarly, HSP's affective estrangement from ordinary perception can yield flashes of phenomenological insight: we may become suddenly aware of the act of observation itself, of the materiality of time, or the contingency of human narratives in a vast, indifferent cosmos. These are not delivered as propositions but emerge tacitly, as realisations spurred by feeling. For example, an HSP episode might build mounting tension with horror-film techniques (ominous sound, the anticipation of a "jump scare") only to withhold the expected release. The viewer, left in a state of unresolved tension, might glean that the actual subject is not a monster that finally leaps out (as in conventional horror) but the tension itself – the way the mind projects threats and meaning into ambiguous stimuli. In this way, the effect (fearful anticipation) becomes a means of knowing something about oneself and the medium: how cinema manipulates expectation and how the human mind grapples with the unknown.

Another theoretical perspective resonant with HSP's affective epistemology is the idea, found in Laruelle-inspired film theory, that "photo-fiction" or film can be a test of one's perceptual fidelity to reality. Laruelle speaks of photographic thinking as "first and foremost of the order of a test of one's naïve self". This cryptic phrase suggests that confronting the photographic (or filmic) reality without the a priori frameworks of standard philosophy is akin to a trial or experiment on our straightforward, natural attitude. HSP's affective onslaughts and confusions test the viewer's naïve habits of sense-making. By refusing easy narrative or moral cues, the films prompt the viewer to reflect on their own reactions and assumptions. One might emerge from an HSP screening with a new self-awareness: noticing how the mind tries to impose a story even on randomness or how quickly emotion attaches to abstract imagery. In this regard, HSP functions almost like a laboratory of perception. Rashidi has referred to using his "own perception and inner life… as a laboratory 'reagent '" in creating these films, and by extension, the audience's perceptions are likewise made into reagents in an experiment. The affective sequences act upon us, and our reflective awareness of those effects completes the experiment, yielding insight.

Moreover, HSP leverages what one might call the materiality of affect. The films often emphasise the physical aspects of cinema – grain, flicker, analogue distortion, droning or shrill sounds – which directly impact the viewer's body. This haptic or visceral quality means that understanding of HSP can be corporeal. We feel the heaviness of a "bone-chillingly gloomy drone" in the soundtrack; we flinch at a sudden cut or the blinding flare of an overexposed frame. Such bodily responses are part of the meaning-making process. The notion of haptic visuality (as theorised by Laura U. Marks and others) is relevant: images that solicit the sense of touch or bodily sensation can convey knowledge that is not linguistic. For instance, HSP sometimes presents extremely grainy, decayed footage where the viewer almost "feels" the image as much as sees it – the decay of the film stock itself becomes an analogue for mortality and memory, grasped at an affective, pre-conceptual level. In Volume 8, as Gocić describes, the series "plunge[s] us into the world of the alternative reality of rapturous, Brakhage-esque visions," where quotidian reality has been "absorbed" and only phantasmatic traces remain. Here, the effect might be one of rapture or vertigo, an overload of visual stimuli that destabilises our sense of what is real. Yet, in negotiating this overload, the viewer potentially gains a negative knowledge – an intuition of how much our sense of reality depends on stable signals and what happens when those signals are scrambled. This is consistent with certain modern philosophies that equate knowledge with the capacity to navigate uncertainty and chaos (e.g., the "catastrophic" knowledge in Nick Land's geotrauma theory, although HSP remains more intimate and human-scaled in its experimentation than Land's cosmic annihilations ).

We can also return to Philippe Grandrieux and the idea of sensation as a form of knowledge. Grandrieux's films (such as Sombre or La Vie Nouvelle) are frequently cited for their intense sensory assault and minimal dialogue, aiming to communicate through affect and corporeal rhythm. Brenez's insight that Grandrieux invests in "immanence" through "sensation" suggests that the way an image feels can carry philosophical weight. In HSP, an entire epistemology is encoded in the patterns of affect. For example, the recurring motif of darkness punctuated by sudden light (scenes that go black and then burst into overexposure) seems to interrogate the very process of revelation and concealment. The viewer's startled physiological reaction to brightness after darkness is the epiphany – a tiny enactment of moving from not-knowing to knowing or from oblivion to insight. Similarly, when HSP alternates between extreme long shots (distant, detached) and extreme close-ups (intimate, invasive), the jarring contrast feels like a question about perspective – the shock of being flung from an impersonal view of humanity to a viscerally personal one. The films thus use form to trigger feeling and feeling to provoke thought.

Finally, HSP's status as an extensive series (hundreds of short films created over two decades) itself contributes to its affective epistemology. The sheer accumulation of episodes builds a kind of immersive encyclopaedia of moods. Watching HSP in aggregate is less about remembering specific events (there are few "events" in the narrative sense) and more about acquiring a tacit familiarity with the grammar of effect that Rashidi develops. Over time, one learns the "alphabet" of this cinema: a cut to black means X, a sudden ominous drone means Y, a lingering out-of-focus shot means Z – not in a fixed code-like way, but as recurrent invitations to certain states of mind. The project becomes a training ground for affective literacy, sharpening the audience's sensitivity to subtle visual and auditory cues. In doing so, it suggests that cinema's philosophical potential lies not only in representing ideas but in cultivating new perceptual capacities in the viewer. This is philosophy as a practice, analogous to how certain philosophical traditions (phenomenology, Zen Buddhism, etc.) see wisdom as arising from disciplined practice rather than abstract argument. Rashidi's practice of filmmaking – iterative, exploratory, and attuned to minute affective textures – models an approach to knowledge that is experiential and processual. The films do not hand the viewer conclusions; they immerse the viewer in an evolving process of sense-making. The viewer's ongoing engagement – including confusion, emotional waves, and moments of clarity – is the site of meaning. In this way, HSP exemplifies how an experimental film corpus can function as a living philosophical inquiry, one where affect and form guide us to insights about perception, self, and reality.

Cinematic Thought at the Limits

Rouzbeh Rashidi's Homo Sapiens Project stands as a singular convergence of experimental cinema and philosophy—a cinema of immanence and thought that pushes the medium to interrogate its own boundaries. Throughout its extensive volumes, HSP pursues a radical project: to discover what film can think and feel when freed from the constraints of storytelling conventions and a human-centric perspective. We have seen how its non-teleological temporality suspends narrative finality in favour of an ever-unfolding present, thereby re-orienting the viewer to the qualitative texture of time. We have explored how its images assert their own ontology as immanent realities, engaging with contemporary philosophical notions that blur the line between image and world. We have considered its adoption of non-human or alien viewpoints, through which the camera becomes an impersonal consciousness examining the human form without – a move that resonates with humanist philosophies and yields an eerie illumination of the real. We have analysed HSP's mode of affective epistemology, whereby the films impart understanding through the very emotions and sensations they evoke, turning the audience's disorientation and fascination into tools of insight.

Crucially, HSP achieves all this without resorting to didactic voice-over or explanatory text; its method is formalist and experiential. In doing so, it exemplifies what one might call philosophy by other means: philosophy is conducted not in the language of propositions but in the languages of montage, lighting, sound design, and rhythm. It echoes the legacy of filmmakers such as Maya Deren, Gregory Markopoulos, and Philippe Grandrieux, who treated cinema as a fundamentally poetic and intellectual medium capable of articulating the ineffable. HSP carries that legacy forward into a new century, amplifying it with Rashidi's unique sensibility. The project's massive scope – comprising hundreds of films that form a single, evolving artwork – itself poses philosophical questions about totality and infinity in art. Is HSP a kind of open-ended Gesamtkunstwerk of the experimental moving image? Does its refusal to conclude (the series continued expanding over decades) suggest that the "limits of cinema" are indeed "not yet tested enough"? The final film of Volume 1 wryly implies as much, noting that even after a chain of introspective dreams, "the odyssey doesn't end there because the limits of cinema have not been tested enough yet". This sentiment encapsulates the spirit of HSP: it is an ongoing interrogation of cinema's own possibilities – an artistic research program into what cinema can become.

In an academic context, one might situate HSP as a form of "film-philosophy" in the robust sense: not just films with philosophical content, but films that do philosophy. As John Ó Maoilearca writes, Laruelle's conception of non-philosophy "opens the door" for creative forms, such as filmmaking, to function as modes of thought on an equal footing with theoretical texts. HSP steps boldly through that door. It operates as a laboratory of thought where each cinematic technique (cut, colour, sound, duration) is a piece of experimental apparatus, and each viewing is a new trial of perception and meaning. The knowledge it produces is non-propositional yet profoundly affecting – a kind of tacit knowing-how in place of knowing that. One doesn't conclude an HSP film with a tidy message; instead, one emerges with one's sensibilities altered one's attention sharpened to aspects of reality (and cinema) that previously went unnoticed.

Finally, the philosophical significance of HSP can also be framed in ontological terms: it interrogates the limit between film and life. Rashidi's work often blurs the distinction between personal diary and abstract cine-poem, between documentation and hallucination. The series as a whole has been called a "film diary" and simultaneously compared to an "avant-garde horror" of metaphysical scope. In navigating these extremes, HSP asks whether filmmaking can be a way of life-thinking—a process parallel to living that reflects on existence through an audio-visual experience. It posits that cinema need not depict a philosophy from the outside but can generate a philosophy immanently through its form. In HSP's montages, one senses a search for what Werner Herzog might call "ecstatic truth" – a truth that is not factual but experiential, arising from the convergence of imagination and reality on film. The Homo Sapiens Project, in this radically philosophical re-description, is not a set of films about Homo sapiens as a species or about Rouzbeh Rashidi as an individual, but rather a searching inquiry into what it is to be a cinematic Homo sapiens: a human being who thinks, dreams, and perceives through the moving image. In this way, HSP ultimately interrogates the limits of cinematic thought not to close them off but to expand them – to suggest that cinema can always think more, feel more, and reveal more as we venture further into its unexplored possibilities. Such is the enduring philosophical provocation of Rashidi's Homo Sapiens Project – a cinema that, in the most profound sense, is alive with thought.